We Paved Paradise and Put Up a Parking Lot: How church assets can be repurposed for the sake of the congregation and the community

/We Paved Paradise and Put Up a Parking Lot:

How church assets can be repurposed for the sake of the congregation and the community

ABSTRACT: The focus of my project is twofold. First, I believe it is important to develop a theology of land and place, so as to understand the significant value most churches hold in their existing properties. Secondly, I intend to explore how churches can identify their theological values so as to utilize the resources in which they are most abundant for the sake of benefitting both the community and their own ministries. This is not necessarily a question of evangelism, but a question of how to create a reciprocal financial and pastoral relationship between congregations and their communities. I will use discipleship as the lens through which to view a congregation’s land/place, so that other churches can use this model to evaluate their own circumstances and opportunities.

Introduction to Ministry Context

The biggest question for our ministerial generation is “What does it mean to be the church?” The dominant ecclesiology in American Churches for the past 200 years has been to grow the fellowship of believers for the sake of apostolic maintenance. But, it is clear that this expression of the church is a failing enterprise. The church does not exist for the sake of growth; it exists to be the expression of God’s love, mercy, and grace in the world. For my congregation, Los Angeles First United Methodist Church, and our circumstances (we own land, but have no building), the question is more specific: can a congregation’s purpose be to teach people how to love God and their neighbor by providing affordable and permanent supportive housing? In the course of this project, I will address the question of discipleship in the modern ecclesiological context. Evangelism is not discipleship, but it can be a result of a faithful discipling community. I aim to address how congregations understand their economic, physical, and congregational resources by constructing a theology of land and place. This project will enable congregations to name both their theological values and their own understanding of discipleship in order to align their goals with their actions.

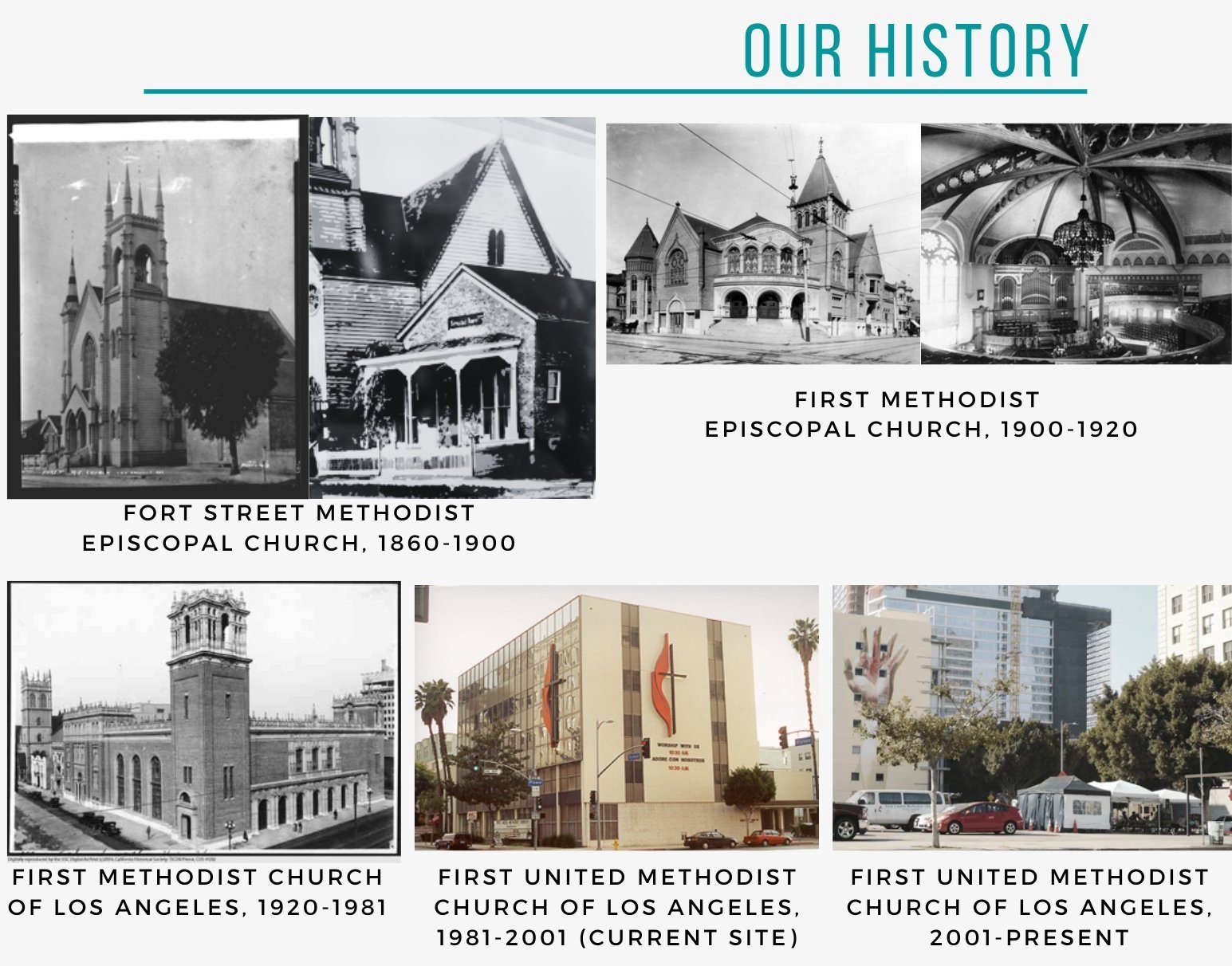

A Brief History of Los Angeles First United Methodist Church

Los Angeles First United Methodist Church was founded in 1853 at the El Dorado Saloon in La Plaza. Sent to “evangelize the rowdy and incorrigible southland.” Rev. Adam Bland succeeded in building a congregation and a building on Fort Street, now Broadway. Fort Street Methodist Episcopal Church was the home of Biddy Mason, an enslaved woman who fought for her emancipation and went on to be one of the wealthiest landowners in Los Angeles in the 1880s. She started First AME in her home, but kept her membership at Fort Street ME Church until her death. Our roots are in social justice, liberation, and love for God and our neighbor.

Fort Street Methodist Episcopal Church continued to grow and serve Los Angeles, and quickly outgrew its first building, which incorporated furnished rooms for people seeking refuge. From its origination, the congregation understood that providing housing for the unhoused was an important reflection of their values. The congregation raised money to build a new sanctuary on Hill Street, and in the early 1900s, raised one million dollars to build a historically significant building on 8th and Hope Street. This building housed their mission, outreach, and educational programs, including the first MCC Congregation and several Korean and Filipino ministries. After the 1960s, the population of downtown Los Angeles shifted due to the economic and transportation changes. The congregation decided to sell their building to the Gas Company in 1981, and purchased the current site, which was an office building on Flower and Olympic. The building was razed due to the lack of resources to maintain it, and the property was paved, so as to serve as a temporary surface parking lot. The Staples Center opened in 1999, which dramatically changed the area around the church’s property, and the parking lot was utilized as a mechanism to generate revenue. Since 2001, the congregation has been worshiping without a building, while also drawing more than enough money from parking lot rent to cover necessary expenses. This unusual model demands a creative understanding of ecclesiology and a critical evaluation of the property and its potential.

2. Explanation of Project and Research Project - Constructing a Theology of Land and Place

“Land is a central, if not the central theme of biblical faith.”

A. Developing a Theology of Land

It is critical for congregations to develop a theology of land and place, so as to understand the significant value held in their existing properties. Walter Brueggemann writes, “Land is a central, if not the central theme of biblical faith,” and most mainline denominational churches are sitting on the most valuable properties in their areas while struggling to pay their staff and utilities, much less fund meaningful ministries. Pastors believe that we are called to serve people, but we are truly meant to serve the people in a particular place. As the neighborhoods change, so should our ministry focus. Developing a theology of land/place is essential for congregations to understand how best to share the Gospel in their context.

The value of land in every major metropolitan area in the United States has changed dramatically. These decisions are politically driven by the white supremacy culture which dominates the power structures of this country. Not only does racism show up in the bones of our government, institutions, and leadership, it appears in our art, architecture, and culture, both secular and religious.

Beginning in 1910, the United States witnessed a number of cities passing ordinances prohibiting the sale of homes to Black people if they were in majority-white areas. The practices of redlining, blockbusting, repossession, and staged burglaries resulted in Black families working twice as hard to pay inflated mortgage payments on installment plans which accrued no equity for 15-20 years. While white families had the option of leaving any time they chose, Black families could not move without sacrificing everything that they had invested in their homes. Meanwhile, white families began to move out of the city center and into new suburbs, new schools, and new opportunities to grow the chasm between the wealthiest and poorest people in society. As the resources of white people fled to the suburbs, so did the churches.

This was true in every major metropolitan area in the country, and Los Angeles was no exception. As Los Angeles’ religious landscape changed, so did the need for support, empathy, and compassion. While the downtown area has seen incredible revitalization over the last several years, the homelessness population has grown exponentially. The results of the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (LAHSA) 2022 Homeless Count estimated that 69,144 people were experiencing homelessness in Los Angeles County, a 4.1% rise from 2020, and 41,980 people were experiencing homelessness in the City of Los Angeles, up 1.7% from 2020. As land has gotten more expensive, the only people able to afford market rate housing are those making more than six figures.

Simultaneously, gentrification is eliminating housing possibilities from those who are most in need. Alan Durning, during a public conversation on gentrification pointed out that “At some point in America, we decided that land is more valuable than people.” This means that land accrues value over time whether or not it has been improved. A house purchased for $250,000 in 2010 could be sold in 2020 for exponentially more money, simply because of the assessed value of the land. The quality of life in America is determined by one’s ability to own a home, which typically leads to generational wealth and stability. Those unable to purchase land are left in the cycle of rentership, and remain in the clutches of affordable housing which could be re-evaluated by the landlord who is more concerned with profit than preservation of his tenants.

Breakfast ministry at Los angeles first UMC

The lack of affordable housing creates a crisis which is felt both socially and ecclesiologically. Additionally, the scarcity of churches in downtown areas – especially in Los Angeles - also means that there is a dearth of institutions concerned with social welfare. David Steven Porter argues that “amid growing socioeconomic inequity in the United States, the ministry of local churches repairs the fabric of local communities.” However, the ways in which churches have repaired the breach between welfare and provision has quietly stitched the fabric of America’s landscape together with raveling thread. The fewer congregants there are to support local congregations, the less aid they can contribute to those most in need. Malcolm Gladwell writes:

Ram Cnaan, a professor of social work at the University of Pennsylvania, recently estimated the replacement value of the charitable work done by the average American church—that is, the amount of money it would take to equal the time, money, and resources donated to the community by a typical congregation—and found that it came to about a hundred and forty thousand dollars a year. In the city of Philadelphia, for example, that works out to an annual total of two hundred and fifty million dollars’ worth of community “good;” on a national scale, the contribution of religious groups to the public welfare is, as Cnaan puts it, “staggering.

The consequences of churches moving out of a community cannot be fully realized. It is of utmost importance, then, to study the examples of churches who have not dedicated themselves to serving particular people (who will come and go), but who are dedicated to serving in a particular place. Churches, many of which own some of the most valuable and strategic parcels of land in urban and suburban areas, hold in their possession the ability to make powerful choices with their assets. Those churches with the ability to adapt to the neighborhood’s evolution will have a much stronger chance of survival.

B. Developing a Theology of Place

There is a fundamental difference in “land” and “place,” and churches occupy both settings. Land holds a particular value and is seen, legally and practically, as an asset. Place, however, is a sociological descriptor that is rich with a variety of meanings. Dolores Hayden identifies that “place” carries the resonance of “homestead, location, and open space in the city, as well as a position in a social hierarchy…Phrases like ‘knowing one’s place’ or ‘a woman’s place’ still imply both spatial and political meanings.” People have been told their place, found their place, stepped out of their place. But, the idea that people can be located - for good or ill - in a place is an intrinsic part of our identities. While our “place” may change, we remain connected to the places which we have called home.

“Our Father in heaven…” The prayer Jesus taught us begins with two important details: to whom and where we are to address our prayers. Christian eschatology defines heaven as home. Identity is centered in both name and place, and our theology is developed in the very question of who God is and where we are to meet the divine. The biblical narrative details the relationship between God and humankind as each generation wrestles with their understanding of who God is. The great I AM is eternal both in name and in location. Where the people are, God is, as well. In the beginning was nothing - a formless void - which was created into something. The swirling mass of nonexistence became a place, where the waters separated to reveal land. In creation, God chooses to be known in a place in history, occupying both chronology and geography.

Public vs. Community Space: Who do you say that I am?

Developing and realizing theologies of land and place are two very different challenges. Once a congregation has examined its history in order to understand how it came to inherit the land upon which it calls home, then the challenge is to occupy, love, and tend the place with equal parts tenacity and gracious detachment. One of the most important things to consider as a congregation discerns its theology of land/place is the distinction between public space and community space. Public space is accessible, comfortable, sociable, and inviting. Community space, on the other hand, implies belonging. There is a clear understanding of boundaries, who belongs, and when and how the space can be used. While most churches advertise that they are public spaces, they are, in reality, communal spaces. Churches have members. Churches have a distinct language for internal communication, and a limited vocabulary for external conversation. In truth, churches are not equipped or resourced well enough to be true public spaces, and most do not have the awareness to be honest about the distinction.

In considering how churches exist in a particular place, it becomes clear that all theology is public theology. Everything about the architecture, landscaping, and design of a property communicates its values to the community. This is especially true during “non-office” hours when the setting itself asks the question, “Who do you say that I am?” This is the conflict most churches encounter: we know that there are unhoused people sleeping on our streets and at our doors, but we are not resourced well enough to open our sanctuaries to welcome them inside. European cities have addressed their public spaces as a resource to be shared rather than an amenity which needs to be guarded. Churches have an opportunity to do this. Our sanctuaries are sacred, and meant to be open to all. Every choice we make about how to guard and protect our space says something about what we perceive to be the threat. Often, the threat is an imagined rampage of an impoverished person, when the reality is that most people (houseless or housed) are simply looking for a quiet place to sit in peace.

If a congregation decides that it would like to create a public space, how could it be augmented so that space isn’t just beautiful, but functional? Cities are often more hospitable to dog owners than to unhoused residents, and churches have the opportunity to create a model for public space that is more like the library (free, comfortable, beautiful, and richly endowed) and less like a museum. How we use our public space teaches us about our values. It is intriguing to consider how a church’s space and land could be transformed into a place that is truly “good” for all people, at all times.

3. Interpretation: Theological Framework and Methodology: Defining Discipleship and Establishing Congregational Values

Once a congregation has established its theology of land and place, the next task is to define discipleship, which is generally understood to be “following the teachings of Jesus,” although each tradition has its own emphasis on how to do so. As a United Methodist, our tradition teaches that discipleship “involves a ministry of outreaching love and witness to others concerning Christ and God's grace. Discipleship also calls the Christian to ministries of servanthood and service to the world to the glory of God and for human fulfillment.” This definition is grounded in Jesus’ teaching about which commandment is the greatest, “‘You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind.’ This is the greatest and first commandment. And a second is like it: ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself.’ On these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets.”

In order to develop a successful theology of place/land, the congregation needs to engage in a thoughtful process of discernment concerning their values. This is not a goal-setting workshop, nor is it a visioning session. Neither of these opportunities are useful until the congregation understands who they are, ecclesiologically and communally. A successful plan will be particular to the congregation and its setting; a successful plan will be actionable and enforceable. Each congregation needs to take the time to know what defines them as Christians, and as Christians together in their setting. What do they share? What do they value? Do they have a shared understanding of their faith journey, regardless of where they are on it? The most successful churches I have pastored have a very clear identity. Everyone who became connected to the church did so because of the congregation’s theological convictions and the consistency with which these convictions were enacted through discipleship and welcome.

Determining the values and hermeneutic

Once the congregation has determined its values, it is important to develop a hermeneutic for making decisions. If there is a challenging decision or option, how will the congregation choose to view the issue? If a congregation adopts a hermeneutic of suspicion, then each question will be examined in order to discover the weakest points. Alternately, if a congregation adopts a hermeneutic of love, then each decision will be made with the question: what do we learn from scripture and the example of Christ about what is the most loving thing to do, for the greatest number of people? If the congregation is primarily interested in making decisions through the lens of discipleship, then it is important to ask: How can our values be manifested in our community, using the congregation’s resources? What are the resources the church has in abundance? How can every decision be made in a way that maximizes our love of God and our neighbor? Each congregation will discover their own framework, based on their character and understanding of God’s call upon their life and ministry. Determining how to be the hands and feet of Christ in the world is critical because every church will understand their values and gifts differently.

Developing a model for ministry

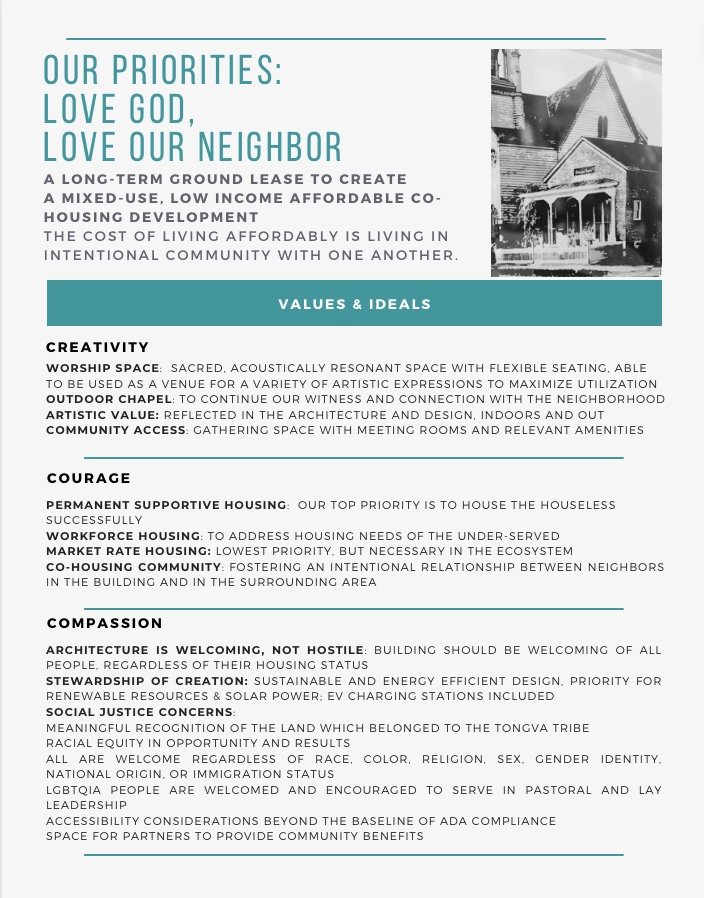

Through our value-setting exercise, our congregation prayerfully discerned that the animating, theological values of Los Angeles First United Methodist Church are creativity, courage, and compassion. Discernment of these primary values helped us to create a model for ministry which generates revenue while also freeing the congregation to live out these values as best we are able, in both the short and long-term. The specificity of our model is not as critical as the carefully discerned theological orientation which led our congregation to make these decisions. It is important for each church to develop a financial model of sustainability which is not primarily dependent on tithes and offerings. It is my congregation’s intent to develop a financial model, as well as a plan for socioeconomically diverse co-housing, which would encourage residents to love their neighbors in meaningful and practical ways.

Based on my church’s history and core values (creativity, courage, and compassion), our intent is to retain ownership of the land, partner with a for-profit developer using a ground lease, and develop market rate, low-income, and permanent supportive housing in a socioeconomically diverse co-housing community, including the parsonage and a worship space. This space will be a true Sanctuary, retaining the openness to the outdoors that we have come to appreciate as a way of demonstrating our commitment to living in solidarity with our unhoused neighbors. When the space is not being used for worship, it should also be functioning as a revenue-generating mechanism, and utilized as a medium-sized performance venue. This plan will take a long time to enact, so in the short term, we have created a hot breakfast ministry, which is consistent with our values.

As each congregation seeks to develop an ecclesiology for an increasingly unknowable future, we have the opportunity to determine our values for the places we serve. As people come and go through our tenures and vestibules, congregations can remain resolute in their determination to live out their values, regardless of who sits in the pews, because God will always meet us there.